This topic was first visited in a February 15, 2019 blog. However, since the Democratic campaign has failed to offer any substance on it and given the Republicans’ stone silence, it is time for a deeper look. Be forewarned, however, that information sources[1] on this topic are generally opaque and even contradictory, so getting to a straightforward quantitative analysis has been difficult. No wonder we can’t get healthcare right. After much digging, here is the possible skinny (from various sources covering from 2016 to 2019, herein estimated for 2018 and rounded ($billions)).

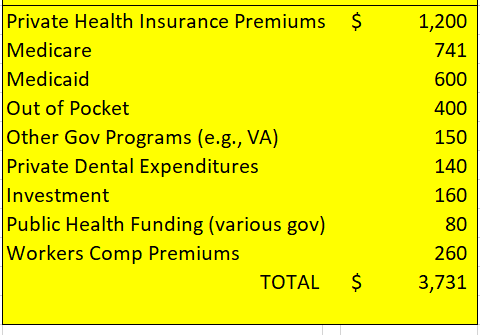

Table 1. Where the Spending Comes From[2]

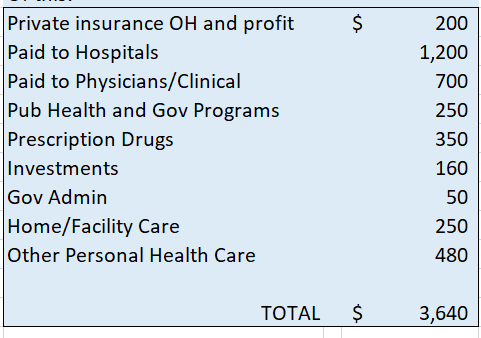

Table 2. Where the Spending Goes

The relative agreement between the two gives some credence, but the source information opacity argues for retaining some skepticism. For example, what is in “Other Personal Health Care”? Nevertheless, it is likely that total US healthcare costs about $3.7 trillion per year.

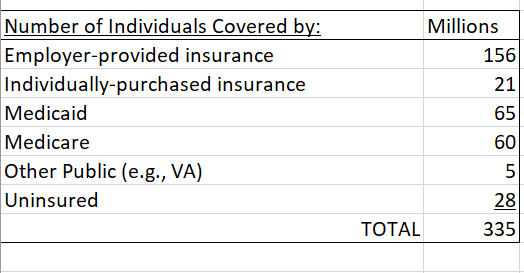

Another important piece of information is how the US population is covered. Again, information sources are all over the place but the chart below is likely to be close (millions).

Table 3. US Population Breakdown of Medical Coverage[3]

The 2018 US total population was 327 million, so Table 3 is pretty close. Keeping in mind that the people noted above pay for health care in various ways[4], the three tables, above, can serve as a database to consider universal healthcare. First, we must clarify some numbers if possible.

Current Costs

Some of the cost line items in Table 1 need some adjustment to understand properly actual current costs. The “out-of-pocket” line item, above, is particularly opaque in the literature, but for this discussion it will be assumed to include: 1) Medicare copays and upgrade premiums; 2) private insurance minimum reserves, copays, refused procedures, and all dental expenditures (a separate line item in Table 1); and 3) costs associated with the uninsured. It will be assumed that a Medicare cost adjustment of just 15% of out-of-pocket costs, $60 billion, is reasonable since Medicare coverage is usually quite comprehensive. It will be assumed that $190 billion of the out-of-pocket costs noted in Table 1 goes to payments for the uninsured by assuming 10% of all hospital, physician, and clinical expenditures pay for their healthcare. That leaves $250 billion of the out-of-pocket in Table 1 for the various private insurance payment gaps and add to that the $140 billion dental expenditures for a total out-of-pocket assigned to private insurance of $390 billion. To recap, the adjusted out-of-pocket (with dental) will be allocated as follows: 1) Medicare – $60 billion); 2) private insurance – $390 billion; 3) uninsured – $190 billion.

At present, percapita Medicare costs with the above out of pocket adjustment and including administrative costs, is $13,400/yr. The 2019 federal Medicare Trustee report for 2018 notes a $13,257/yr “average benefit per enrollee.” Private insurance costs $10,500/yr per person (private and workers comp premiums including the out of pocket adjustment noted above for a total cost of $1.85 trillion/yr divided by 177 million people). These 2 items total $2.7 trillion. Adding the other current costs in Table 1 (e.g., Medicaid, investment, public health, etc.) gives $3.7 trillion, thus reconciling with the Table 1 total.

Future Costs

Now consider what universal healthcare might cost. Assume a universal health care program that includes a Medicare option open to all (“New Medicare”) and continued private insurance offerings. New Medicare would include all current Medicare beneficiaries plus those in Medicaid, the uninsured, those covered other ways (e.g., VA) plus 22 million people who might switch from private insurance to New Medicare. That would put about 165 Million people on New Medicare, and about 160 Million people on private insurance – essentially half the US population in each.

A straight calculation with current unit costs for this new system would total $3.9 trillion (165 million people x $13,400/person for New Medicare + 160 million x $10,500 for private insurance). That is $200 billion/yr more than current. Efficiencies might be possible not only to match current costs but actually to go lower. Consider this:

- The new, younger demographics of an expanded Medicare (“New Medicare”) might reduce percapita costs, although a larger membership might raise administrative costs. If a 10% overall reduction could be gained, $300 billion could be saved.

- If prescription drug costs could be negotiated and thus cut 30% (they are up to 90% cheaper in other countries), $100 billion could be saved.

- If private insurance profits could be squeezed and with lower overhead associated with a smaller provider census (i.e., out of the $200 billion profit and overhead line item, above), perhaps $25 billion could be saved.

- If hospital procedure costs could be negotiated and standardized instead of today’s wild variations in a totally opaque system of costs, perhaps 10% could be shaved off hospital expenditures, or $120 billion.

- If the inefficiency of indirectly paying for the uninsured was eliminated by insuring them on New Medicare, perhaps 20% of the current out-of-pocket line item could be saved (assuming that is where the cost of the uninsured is currently located in Table 1), or $80 billion.

These possibilities total $625 billion, which would make a total future cost of $3.3 trillion/yr for US healthcare costs. Thus, not only can universal healthcare add no new costs, but a leader with a sharp pencil could actually make it cheaper than it currently is. Although some payments may need shifting around (e.g., averted private premiums shifted to taxes) absolute costs per person or company should not change and to argue otherwise is a red herring. Also, to consider universal healthcare in 10-year terms, as is the candidates’ practice, is an obfuscation combining 2 different issues – growing costs and how they’re paid.

Presumably, a US universal healthcare system would be blind to preexisting conditions. It should also continue with employer contributions to healthcare costs since this somewhat unique US practice represents no new burden and has a rationale that employers need to keep their workforce healthy. Also, the above analysis eliminated out of pocket costs by shifting them ultimately to either New Medicare or to private insurance. Let’s keep it that way. Cost creep through out-of-pocket expenses such as minimum reserves and copays is the crack in the door for the corrupt payee abuse that we’ve seen over the past 30 years where, for example, visit copays have risen from originally incidental to what used to be the full cost to go to the doctor. Build it in, get rid of it, don’t let the abuse back in. Finally, what’s covered, and prompt service must be addressed to ensure US universal coverage doesn’t suffer from complaints elsewhere in the world.

Hopefully, the government can provide

such a good New Medicare option (as Medicare currently is) that private

insurers will be forced to improve so as to retain their customers and overall

costs will decline. If costs do go up, or

if this analysis is somehow wrong, how much are people willing to pay

additionally for universal healthcare?

[1] Sources used included the government’s Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), the Kaiser Family Foundation, the AMA, the ADA, and an annual federal government report on the Medicare Trust Funds, among others.

[2] “Medicare” is the value given in the federal Medicare Trust Fund Report for the year 2018 of Medicare benefits paid plus administrative costs. Part A benefits were $308 billion, Parts B, C, and D were $432 billion. Part A is paid for from payroll taxes while the others are paid for by premiums and general federal taxes; combined, overall as 36% from payroll taxes, 43% from government “general funds”, 15% from premiums, 6% from “other” (more opacity) including some trust fund investment income.

[3] The value given for Medicare is from the federal Medicare Trust Fund report covering 2018. It includes about 20 million people on Part C, also known as “Medicare Advantage.” Part C constitutes numerous private health insurance plans where the private insurance companies are reimbursed by Medicare. Presumably, beneficiaries decline Part B in lieu of cheaper Part C premiums that the private insurers run mostly like HMOs to reduce costs and thus reduces overall Medicare costs.

[4] For example, employer-provided insurance usually has an employee-paid component, costs for the uninsured are paid in various public and private ways, nearly all costs have an out-of-pocket component, and there are various government-sponsored programs, including Medicaid.