Simpler Tax, Balanced Budget.

Can we fix our byzantine tax code and the national deficit? Many states already have balanced budget requirements, why can’t the Feds? Maybe debt is good because it results in reliable (so far) investment instruments. But we could have no (or limited) annual budget debt while still offering bonds for things like infrastructure. Currently our dysfunctional Congress not only can’t issue a budget (Congress has passed only 4 complete budgets in the past 40 years, relying instead on the lifeboat called “continuing resolutions”, which is what leaves us vulnerable to government shutdowns), but they also are shooting our deficit through the roof. This is a crazy way to run a government and leaves the average citizen at a loss to understand or have a say in spending and revenues.

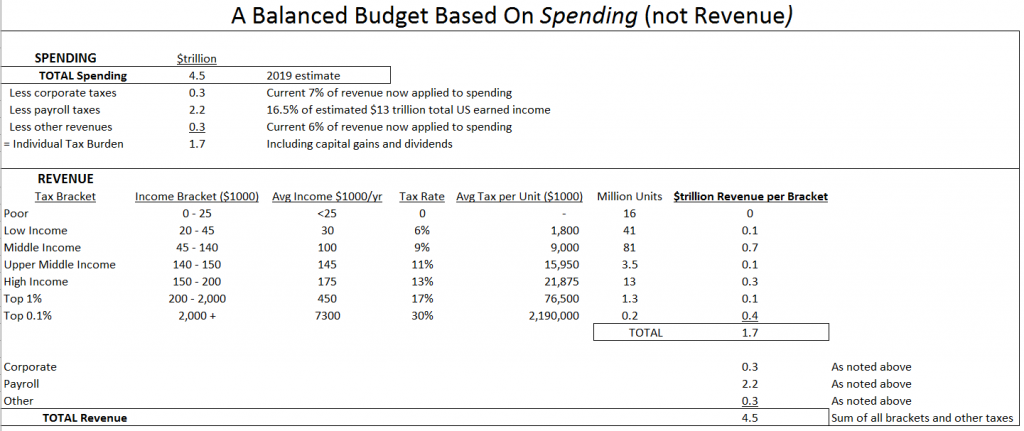

The solution is to make next year’s tax burden, in dollars, equal to last year’s spending. This can be paid for by a progressive tax with no deductions or other types of “loopholes”. This approach will have 2 dramatic benefits: 1) a balanced budget; and 2) direct feedback to the taxpayer about spending, i.e., taxes go up when spending goes up, so if your taxes go up ask your reps what spending went up? No more hiding in Washington.

Before getting into how it might work, consider some facts (there may be some inaccuracies or discrepancies, but this is the best you get on the internet):

- In 2019, the US will spend $4.5 trillion.

- 2020 US tax revenue is estimated at $3.6 trillion

(thus, the deficit of about $1 trillion):

- 7% from corporate

- 51% from individual/joint

- 36% from “payroll taxes” that pay for Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance (SMU)

- 6% from things like estate taxes (2%), excise tax, and tariffs (4%).

- 54% of total federal spending is for SMU:

- 24% for SS, 15% for Medicare, 15% for unemployment benefits.

- At 54% of spending but 36% of direct revenue (payroll taxes), there is a gap of 18% on SMU spending that comes from general federal tax revenue or deficit spending.

- Payroll taxes total 16.5%, shared by employees and employers: SS – 6.2% of employee earnings each from employer and employee (capped at $133,000 of earnings); Medicare – 1.45% of employee earnings each from employer and employee; unemployment insurance – 1.2% of employee earnings from employer.

- In 2015, 140 Million taxpayers (“taxpayer units”) earned $13 trillion and paid $1.5 trillion in individual/joint income taxes. (There are wide variations in these estimates.) Presumably the difference between that number and 51% of $3.6 trillion ($1.84 trillion) is capital gains and dividend tax.

- At $13 trillion of total income, the average income of a taxpayer unit was $93,000/yr ($13 trillion divided by 140 million units).

- The average (not median) percapita income in the US is about $50,000/yr.

- In 2015, the top 50 percent of all taxpayers paid 97.2 percent of all individual income taxes while the bottom 50 percent paid the remaining 2.8 percent.

- The top 1 percent paid 39% of individual income taxes compared to 29% paid by the bottom 90% (presumably that means that the other 32% was paid by the next top 9%)

- Although there are many versions of this, one source said 29% of households (taxpayer units) are “low income” ($20- $45,000/yr); 58% are “middle” ($45- to $140,000); 2.5% “upper middle class” ($140- to $150,000); and 9% “high income” ($150- to $200,000). The top 1% (1.3 Million taxpayer units) made an average of $450,000/yr; the top 0.1% earn an average of $7.3 Million/yr (there is clearly a wide variation in this bracket).

- The federal poverty limit for a family of 4 is about $25,000/yr. Households making less than this are eligible for additional money such as food stamps or an earned income tax credit.

- An estimated 38 million people live below the poverty line. This is 12% of the US population and these people may not even be counted among the 140 million taxpayer units. People below the poverty line are eligible for government assistance, such as food stamps and earned income tax credits, which is an interesting way for the government to subsidize business by keeping a low minimum wage.

Federal subsidies for those below the poverty limit (e.g. food stamps) is an interesting consequence of the Federal minimum wage. Essentially, the Feds subsidize business by allowing them to pay such low wages that workers can’t afford to live without government handouts. Business gets to save money by underpaying workers, while taxpayers foot the bill. Sounds like federally-mandated Socialistic Capitalism. Just an observation, not part of the fix described below.

A Simple Solution

The US could have a balanced budget with an average individual/joint tax rate of 13% while keeping the percentage of federal income rate from other taxes (e.g., corporate) the same as present. Note, however, that although such other taxes would contribute the same percentage as present, their actual dollars would increase because the balanced budget would require it to be a percent of spending, not of revenue. To avoid the individual/joint tax being regressive, consider the following rate progression according to income bracket:

In the table above, “individual” taxes are either individual or joint returns (“tax units”), estimated at a total of 140 million. Individual taxes in the table include capital gains and dividend taxes, but these could be separated from earned income tax in a more complex scheme if it is believed that lower capital gains tax meaningfully incentivizes investment. It is true that this scheme would increase the real dollar amounts paid by other taxes, such as corporate and estate, due to a switch if their percentage rate applied to spending rather than revenue. But why shouldn’t corporate tax money be higher when companies are obviously making so much money that they can afford $100 million golden parachutes? And arguments can be made that low estate taxes discourage economic growth. The alternative is to beat it out of the working poor and middle class or to increase debt, which is essentially kicking the problem to future generations (which happen to be our children, by the way).

This proposed approach offers transparency for spending, something we lost years ago even before Congress went to sleep.